|

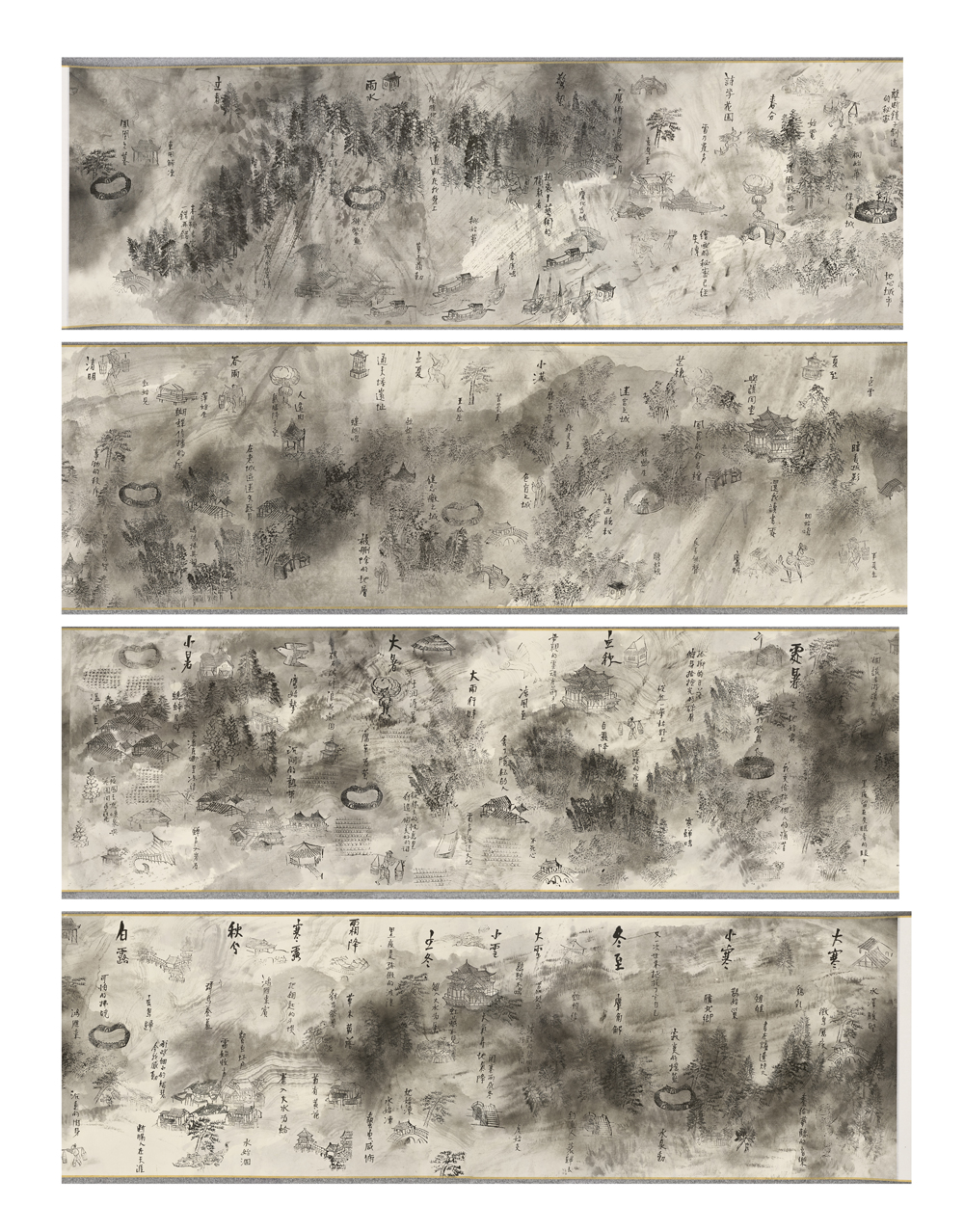

Seventy-Two Pentads |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Seventy-Two Pentads The work Seventy-Two Pentads employs 72 natural phenomena corresponding to the Twenty-Four Solar Terms as its framework, creating an unfolding scroll that is alsoconnected end to end-- Time flows onward and also cycles.All seventy-two "phenological signs" primarily depict the behaviors of flora and fauna: the arrival of migratory geese, the chirping of cicadas, the emergence of earthworms, the blooming of peach blossoms, the growth of duckweed, and the ripening of grain, etc.Each solar term spans 15 days, and roughly every five days, a natural phenomenon occurs, such as which bird starts to chirp or which insect starts to burrow out. This system represents ancient China's meticulous yet imaginative observation of nature, rife with charming inaccuracies—a fantastical imagination reminiscent of the Classic of Mountains and Rivers , such as eagles transforming into turtledoves, sparrows turning into clams when diving into water, and so on.The ancients declared these with absolute conviction, as if they were indisputable facts—and later generations never bothered to correct them. Why? Why?I suspect it's because these observations were largely confined to the Yellow River Basin , yet people understood the vastness of All-Under-Heaven. In a world so immense, where wonders never cease, who could say with certainty that in the southern Baiyue lands or the western Kunlun Mountains, eagles couldn't morph into doves, or sparrows couldn't turn into clams?The Seventy-Two Pentads originate from the "Yizhoushu: Explanation of Seasonal Observations", a Han Dynasty text revised and expanded over time. Its compilation period isn't far removed from works like In Search of the Supernatural or the Classic of Mountains and Seas . Thus, I'm convinced that within these "erroneous" observations lies a humble imagination of the unknown—a humility not unlike our modern-day awe before black holes and supernovae. Across different sections of the scroll, I distributed small woodcut-printed stamps that I had pre-carved. These stamps depict not only details of human life—walled cities, pavilions, fields and bridges, boats and villages—but also pine trees, bamboos, and various unnamed plants commonly found in classical Chinese landscape paintings. Among them also appear elements never seen in ancient artworks: flying fish, mushroom clouds, sea monsters, crocodiles, and the like." The Seventy-Two Pentads follow a chronological order, forming the basic framework, interspersed with abundant annotative texts. This work represents a contemporary Chinese literati's ideological melting pot. This melting pot encapsulates a perception of cosmic spacetime, embodying a consciousness of “All-under-Heaven”- though what constitutes “All-under-Heaven” today is the post-Columbian Exchange world. It is an era where the ghosts of empires wander through Central Asia , transforming natural surveys and archaeological endeavors into political-military activities. In the increasingly blurred borderlands of empires, human wandering manifests as trade, intermarriage, encounters, and the perpetual migration of knowledge, accents, and beliefs. Within the composition, the small stamped images and annotative texts conceal numerous literary allusions. The phrase “monopolizing the secret of mirror-making” refers to how Venice developed crystal glass, enabling it to manufacture mirrors. Fearing the leakage of this manufacturing technique, they confined all glass artisans to the island of Murano . The phrase “diseases spread by butterflies” metaphorically references the Columbian Exchange. Consider how our sunflowers, peanuts, tobacco, and coffee all originated from South America, while the Old World primarily brought smallpox, malaria, and typhoid fever to the New World . It was the pathogens carried by the Spanish that decimated countless Indigenous populations. The “ruins of the Tower of Babel ” naturally refer to the legendary Babylonian tower. The phrase “lost for months in the old city” refers to Old Delhi – its labyrinthine alleys are so entangled that one could truly lose oneself there for an extended time. The line “The secret passage is within my body” is delivered by Maggie Cheung in the film New Dragon Gate Inn . When I wrote the text “The secret of painting has been lost", I was thinking of Pamuk's novel My Name Is Red . "When I wrote“the secret of painting has been lost”, I was reminded of Pamuk's novel My Name Is Red . When all these fragments are pieced together, they paint a worldscape of shifting civilizations—where countless individual destinies are swept into its churning currents. Here, the individual is rendered insignificant; fragments are scattered everywhere, each with its own origins, yet few would bother to trace them. Such is the world it portrays. All these fragmented annotations—some penned by myself, others dredged from half-remembered readings—intruded abruptly during the painting process. Among them are classical Chinese phrases like “reading paintings and scenting incense” or “ Sanctuary of Reclaimed Scholarship (the name of a pavilion in a Suzhou garden, itself inspired by verses from Su Shi or Tao Yuanming)”. These fragments of literati life intersect with Silk Road travelers, missionaries bordering on heresy, the “City at the Earth's Core” from sci-fi realms, ambitious schemers, stargazers, fortune-tellers, wizards, and gentleman scientists—all converging at the frayed edges of civilized empires. Here they barter for survival, yet remain driven by distinct fates: forces of geography, climate, and history. The system of 24 solar terms and 72 peadats,whether born of meticulous observation or imaginative construction, naturally embodies a consciousness of cosmic order. It resonates with what Yan Fu described in his preface to Evolution and Ethics :“All scattered beings must exhaust their heavenly-endowed capacities to preserve their own kind.”—that vibrant sense of Darwinian struggle.Every plant, animal, and tiny insect lies dormant, and when the time comes, they'll pop out to cause mischief and stir up trouble. As we gaze within this tiny garden, thoughts of the entire world arise — all because we see leaves falling from the trees.As we witness butterflies drifting in and insects stirring to life, our minds expand to contemplate the whole world and the entire empire – indeed,“seeing ice form in a bottle, one knows the coldness of all under heaven”. Then it occurs to us: at the edges of empires, strangers infiltrate as plant hunters; a mother's spirit wanders ahead; heartbroken souls drift at the world's end; thunder rolls across the land. Diverse phenomena, myriad signs—auspicious portents and ominous warnings, meteors or unfamiliar dances accompanying missionaries. Here, minerals are discovered; there, rebellions erupt. These manifestations are distributed throughout our world, much like the seventy-two natural phenomena embedded within the twenty-four solar terms. Thus, such annotations may be seen as my additions to the Seventy-Two Pentads. "For example, “The City of Colorblindness” was a story I created about enlightenment during my freshman year in a comic book class. Somewhere in the world, there existed a city where all inhabitants were colorblind, utterly unaware that the world possessed color. One day, the city lord's daughter ventured out to play and encountered a stranger by the river—a handsome prince on a white horse. A miracle occurred: the moment their eyes met, the young woman perceived color for the first time. Suddenly, she saw the blue of the sky and the white of the horse. Upon returning, she became overwhelmed with frustration, insisting, “There are colors! Why can't you see them?” The people deemed her mad and confined her. Later, the city was consumed by fire, and its scattered inhabitants dispersed across the world, becoming the colorblind people of today. This “All-under-Heaven” is a chaotic collision of myriad destinies—a relentless turbulence and cosmic awareness that evokes the farthest reaches of the world. A traveler, perpetually whipped by irresistible forces: the tyranny of time, the weight of geography, the grip of empires, all descending upon their burdened flesh. Caught between heaven and earth, they are utterly at the mercy of circumstance. Everywhere things crumble—the order of things, the past itself—while new chaos ceaselessly births itself. Yet through it all, the rhythm of time endures. Braudel once said, “The Mediterranean is the true master of the Mediterranean .” Indeed, the Tarim Basin too is the master of itself. As travelers on this earth, even our planet is not free—whirled in endless circles by the sun's gravitational pull. This makes spring inevitable, the emergence of earthworms inevitable, the drying of oceans inevitable, and the freezing of soil inevitable. Yet even the sun is not free; it too has its destiny: to burn, to cool, to vanish into silence. Only the diseases brought by butterflies could have been avoided.

|